|

|

|

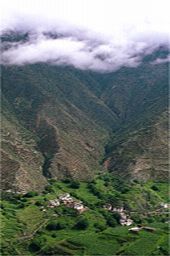

Height of luxury in Shangri-La

The opening of two five-star resorts on the Chinese border with

Tibet has put the spotlight on this beautiful but troubled region.

Mark Townsend reports

How I miss air. Life seems so much more straightforward with a sufficient supply of oxygen.

Gasping with the exertion of flopping from my colossal double bed,

I crawl across my Tibetan mansion and dial room service.

Two deodorant-style air canisters complete with plastic face mask arrive promptly.

Reunited with the ability to move as nature intended,

I venture out into the rarefied atmosphere of China's Yunnan Province.

If inside was breathless, the world beyond is breathtaking.

A sweeping valley of yellow mustard flowers winds towards steep, pine-smothered slopes.

In the distance, the grey spires of snow-streaked peaks rear up, summits stretching into an impossibly blue sky.

Small figures in vivid pink headscarves can be picked out among the fields,

wandering the same narrow tracks their ancestors have followed for centuries.

It's a scene of such pastoral perfection that time itself feels frozen.

Here, amid the foothills of the vast central Tibetan plateau, is a place touched by magic,

a land of undiluted beauty that is said to have inspired one of the great myths of modern times.

This was Shangri-La, the inspiration for

James Hilton's 1930s novel Lost Horizon

, which depicted an isolated mountain paradise where time wound so slowly that its people lived for centuries without

so much as a postcard from the outside world.

Though famed for his imagination, even Hilton could not have envisaged a time when his countrymen

could jet into this remote kingdom, stay a couple of nights in a renovated Tibetan lodge before

musing over which of the 21 light switches best illuminated the journey from the 4ft deep dark-wood

bath to the well-stocked mini-bar. Neither could he have foreseen a time when visitors to Shangri-La

would order bottled air from a bedside phone. Luxury travel has finally arrived in one of the most

undiscovered corners of our shrinking globe.

I am one of the first visitors to the Banyan Tree resort in Ringha, a high-altitude valley

close to the nearby town of Shangri-La. It is one of the highest luxury resorts on the planet.

In this elevated enclave, the air itself induces a tranquility, lack of oxygen effortlessly

coaxing the mind to a dreamlike state. The intensity of light, which initially seems to sting

the eyeballs, only heightens the other-worldly experience.

Soon even the subtle contours of faraway hills become crisply defined, small pine trees resembling

bobbles of shade and light on the vertiginous slopes that loom on all sides.

More mundane observations follow. In this rarefied domain you learn that cigarettes smoulder

for 40 per cent longer than in the hullabaloo of central London. Local wines seem doubly eager

to take effect. Wheezing honeymooners may have to display a shared patience as their bodies adjust

to such giddy heights.

But in this mystical world of beauty and light, shadows linger.

Long before the arrival of moneyed Westerners, this is a place whose culture,

whose very way of life, has been suffocated by a foreign invasion of an altogether different type.

Much has been written about the Chinese oppression of Tibet, mostly relating to the tumultuous

events of the past 60 years. After China invaded in 1950, it declared Tibet a 'national autonomous

region' under the notional rule of the Dalai Lama, but in practice run by the communists in Beijing.

Brutal repressions followed, leading to charges of genocide, land was seized, thousands of monasteries

were closed and monks evicted.

The result is that behind the montage of the pink headscarves, golden crops and multi-coloured Tibetan

prayer flags scattering their good wishes to all humanity, a grimmer reality exists. The valley of the

river Shudugang where the Banyan Tree resort lies is in an autonomous Tibetan prefecture in China's Yunnan province.

Mention China's policies towards Tibet and the bright eyes of the villagers cloud over, their gaze dropping

to their dusty boots. Tour guides similarly choose to deflect any talk of Beijing; the topic

is deemed 'too political'. The most that they will venture is that Tibet's Buddhist monasteries

can be built only with permission from the Chinese authorities. Similarly, that major Buddhist festivals

require sanctioning by the state.

More sinister are claims that Chinese officials have 'spies' planted in religious buildings,

one ear cocked for dissidents talking about the Dalai Lama, the exiled Tibetan leader forced

to flee his homeland as Chairman Mao embarked on a political doctrine of intolerance that almost

vanquished Tibet's unique culture. Even in the serene fields of the Ringha valley there is talk of

Chinese 'watchers' in the community.

Although China may be presenting a new outward-looking face to the world, some things,

it seems, may never change. Those behind the Banyan Tree's excursion into this rich but

complex region will no doubt appreciate that certain facets of history can never be dismissed

as a past irrelevance.

There is irony also that, more than half a century after China attempted to strip

Tibet of its native culture - the anti-religious Cultural Revolution was followed

by violent repression of protests - its government has allowed the construction of

a luxury resort which lovingly recreates the architectural details of a traditional

Tibetan village for the outside world to visit.

On a positive note, the arrival of Banyan Tree in Ringha appears to have benefited the

valley locals, a number of whom are employed at the resort. Its traditional mud-brick

houses were procured from nearby villages and reconstructed by Tibetan craftsmen on a

steep hillside above the Shudugang river. Locals were so amply compensated that many

are now upgrading their own homes to the equivalent of Chelsea mansions.

Inside these towering properties, smoking cauldrons of yak butter tea are tended

by women with ruddy cheeks scorched by the elements.

So novel is the appearance of fair-skinned foreigners in these remote villages that

visitors will find themselves gawped at. Children rarely fail to stop and stare at

these strange figures shuffling through their narrow, sun-scorched streets.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that China's belated tolerance towards Tibetan values is

based on an appraisal of the culture's value to the country's economy. After all, a way of

life that has exerted such an enigmatic hold on the minds of Western travellers offers the

prospect of fresh tourist dollars. It's too early to tell whether Shangri-La could become

some sort of Chinese-controlled Tibetan playground preserved only for the likes of rich tourists.

We had arrived in Shangri-La after a four-hour journey from Lijiang, deep in Yunnan province.

The road trip takes you into the heart of the tectonic turmoil that shaped the planet.

Here, tumbling from the vast plateau of central Tibet, three of Asia's great rivers -

the Yangtse, the Mekong and the Salween - career in parallel just 50 miles apart.

Lijiang, basking under never-ending blue skies, is a town of cobbled streets,

ancient stone bridges and tiled rooftops that has become one of the tourist phenomena

of recent years. Here, hordes of Chinese wander in search of a sepia-tinged land they

have read about but rarely seen. Squint and Lijiang resembles a charming Tuscan hilltown,

complete with camera-touting tourists. Do the same amid the surrounding rustic landscape

and you could be convinced that you are in the heart of the Dordogne.

But Lijiang and its Disneyfied presentation of Old China offers, possibly, a glimpse of

Shangri-La's fate. Among the stalls selling cured yak meatballs and deep-fried chicken's claws,

visitors can be spotted clutching KFC family buckets. An Oasis track can be heard blaring from an unseen alley.

The Banyan Tree hotel has just opened and, like its neighbour to the north, is unswervingly

impressive as a luxury retreat. Evenings can be spent in your own outdoor Jacuzzi, watching

the sun drop behind the thrusting frame of the 17,000ft Jade Dragon Snow Mountain whose

soaring upper flanks have still to be touched by man. Days can be whiled away in the classy spa,

trekking or visiting the nearby world heritage site dedicated to remembering the indigenous

Drongba people. Be aware of the warning signs, however: 'Illegal activities such as fighting

and ratbaggery are prohibited.' Another tells you that 'daubing' is particularly frowned on.

In Shangri-La itself, though, the Tibetans seem to be doing a grand job of making sure they

will always be remembered. As dusk swoops on the town's ancient square, thousands have

recently begun congregating to dance just as in the old days. It is a stirring sight as

old men, most of whom had forgotten their traditional steps in the decades China banned

such expression, mix joyfully with grandchildren and teenagers. Everyone seems to be there:

bank managers, police officers, shopkeepers, all whirling around to a gloriously uplifting

beat as if their very way of being depended on each moment of each song. Close by, Tibetan

restaurants such as the Potala Cabin are packed with patrons chewing dumplings of yak meat,

a surprisingly tender dish considering the hardy, aged beasts from which it originated.

Much of the town's food comes from its main market, where mountains of cabbages sit alongside

sacks of chilli seeds and vast cones of yak cheese. Seafood, however, is conspicuous by its absence.

Tibetans bury the bodies of loved ones in rivers, ceremoniously chopping up their flesh before they

are whisked away on the current towards reincarnation.

Above the market and Shangri-La's twisting streets stands the Ganden Sumsanling monastery,

its golden domes reflecting the fiery scarlet of another unbroken sunset.

Its impressive ramparts have watched over the town's people for centuries.

Little has changed - until now.

Even when Tony Blair came to power, Shangri-La was still being described as the archetypal

one-horse town. Back then, motorised travel meant flagging down a lift in the policeman's

sidecar. The arrival of the Banyan Tree and the opening of a modern airport will ensure

that Shangri-La quickly stumbles from the stuff of legend into the consciousness of a

curious wider world. Like much of China, it won't stay like this for long.

The Observer (02.04.2006)

|

|

The Banyan Tree resort,

Ringha ... in a remote

corner of the Himalayas.

|

|